The question arises not infrequently in clawhammer discussions as to whether or not it’s a good idea to have a “scooped” banjo.

Now for those unfamiliar with this term, it refers to replacing the higher frets (typically those above the 17th fret, though this is widely variable) with a lowered section of the fretboard. (While it is normally only the fingerboard that is affected, it’s usually called “scooping the neck.” The Deering Goodtime banjo is an example of a banjo having no separate fingerboard, so in its case, it truly is a scooped neck.)

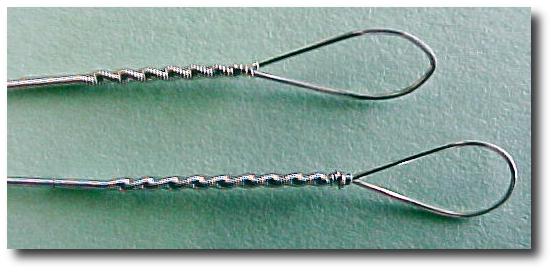

Here are two scoops: the one on the left, by Mike Ramsey, is straight across (roughly above the spot where a 17th fret would be if this were not a fretless banjo) the other being an Ome Northstar having an “S” scoop, being scooped above the 17th fret on the 1st-string side, and above the 15th fret on the 5th-string side. (BTW, please note how Mike Ramsey tapered the inlay right into the “ramp” of the scoop. How cool is that?)

One can see from these side views of these same two banjos how the fingerboard has been removed (“scooped”) below the point the bottom of the fret tangs (or where they would be) .

(Click on photos to enlarge)

Naturally, one might wonder: “OK, very nice, but why on earth would someone want to remove part of the fingerboard and a bunch of frets (or, FTM, to buy a new, scooped banjo made without those frets)?”

As so often happens, there is more than one answer:

- It allows the player’s right hand easy access to the strings without his fingers or thumb striking the fingerboard when playing “over the neck.”

(Oops, we just raised another question: “Why on earth would someone want to play with his right hand over the neck?” That, at least, is a very simple question to answer: for tonal variation. As it turns out, the closer the right hand is to the bridge when striking the strings, the brighter the tone of the instrument. In fact, if you get too close, the tone becomes quite thin and tinny.

Conversely, as the right hand moves away from the bridge towards the halfway point at the 12th fret, the tone becomes softer and warmer. Many clawhammer players like to use their instruments’ full spectra of tone, rather than just keeping their right hands in one place as they play. Having a scoop makes it easy to find the warmer tones when desired.

Too, as one strikes the strings roughly above the 19th fret’s nominal position, one often hears a hollow, popping sound that is commonly called the “cluck.” Again, having the right hand up over the neck makes this far easier to accomplish.)

- Oh, yeah, another reason to have a scoop…it looks ever-so cool.

This scooping of necks had been done occasionally over the years, but it was the playing of Kyle Creed and his subsequent building of banjos for sale that brought them to people’s attention. Subsequently, when Mike Ramsey began to build banjos specifically for the then up-and-coming old-time music market, he added a couple of Kyle’s touches to his banjos: scooping them and promoting the 12-inch pot.

Are there reasons not to scoop a fingerboard? Sure! I would never scoop a vintage instrument. Likewise, if you can only have one banjo and you frequently play above the 17th fret, having a scoop would be quite limiting.

Many clawhammer players rarely play above the 7th fret and never above the 17th, but still don’t want to scoop their banjos (because they have vintage instruments, or because they don’t like the look). Many of these people simply install a tall bridge, raising the action significantly up the neck, but not down in the lower positions where they play. In this way, they can get the same tonal advantages of a scoop, but without having to alter their instruments or buy special ones.

Others of us like relatively low action everywhere, in which case a scoop is wonderful, because we have full tonal range but are not limited to playing down at the first few frets.

When the question of scooping was recently raised in a Facebook group, I threw together this dichotomous key to assist in the decision of whether or not to have a scooped banjo:

1a) I don’t like the plunky sound people get when playing over a scoop…NO, DON’T GET A SCOOP

1b) I like–or could like–that sound…go to 2

2a) I really don’t like the way a scoop looks….NO, DON’T GET A SCOOP

2b) I either like the way a scoop looks or I really don’t care one way or the other…go to 3

3a) I sometimes play above the 17th fret…go to 4

3b) I never play above the 17th fret…go to 5

4a) I am limited to having only one banjo…NO, DON’T GET A SCOOP

4b) I play several banjos, and can always play above the 17th fret on another instrument if needs be…go to 5

5a) I am not comfortable trying to move my right hand to different positions to vary tone…NO, DON’T GET A SCOOP

5b) I’m willing to try something different and want to access the widest tonal range from my instrument…SURE, GO FOR IT!

All that said, I really like having scoops on my modern banjos. I like the warm tone available there but frequently play back closer to the bridge. This photo of my everyday banjo’s head shows pretty well how much I move my right hand about. The photo of the scoop shows (if you look closely) the wear (well, really they’re just clean spots) between the strings and on the fingerboard’s edge where my fingers and thumb make contact.

(Click on photos to enlarge)

Bottom line–if you like the idea, why not try a scooped banjo?

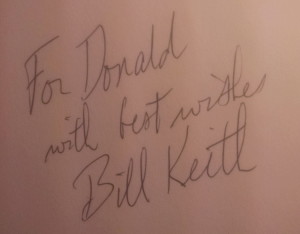

According to Bill, the first person to notice was–naturally–Mr. Scruggs himself.

According to Bill, the first person to notice was–naturally–Mr. Scruggs himself.

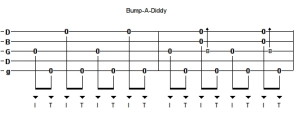

It’s quite a simple approach: One picks upward on a single string, then a beat later brushes a chord down across several strings using the back of one’s ring (or other) finger, which is in turn followed a half beat later by the sounding of the 5th string downward with the thumb.

It’s quite a simple approach: One picks upward on a single string, then a beat later brushes a chord down across several strings using the back of one’s ring (or other) finger, which is in turn followed a half beat later by the sounding of the 5th string downward with the thumb.  ply “diddy diddy diddy diddy,” i.e. a stream of eighth notes (occasionally interrupted by leaving out an eighth note for emphasis).

ply “diddy diddy diddy diddy,” i.e. a stream of eighth notes (occasionally interrupted by leaving out an eighth note for emphasis).

They recently completely revamped their site, and this page apparently no longer exists, but it’s sort of interesting to see who was (and most likely still is) buying their wire for strings. This implies, of course, that if you buy a 0.010 first string from GHS or D’Addario, or DR, or Ernie Ball, or Gibson, etc. you’re getting exactly the same wire!

They recently completely revamped their site, and this page apparently no longer exists, but it’s sort of interesting to see who was (and most likely still is) buying their wire for strings. This implies, of course, that if you buy a 0.010 first string from GHS or D’Addario, or DR, or Ernie Ball, or Gibson, etc. you’re getting exactly the same wire!