Herewith, I present Sig. Antonio Berlese, Italian entomologist of the 19th & 20th Centuries:

1863-1927

Nope, that’s not me, and while I do see some similarities, my normally close-cropped fringe hairs are, at this writing, down to my shoulders. Thanks, COVID! Oh, also, while I never wear ties, I do wear glasses.

So who was this dashing entomologist? And what does he have to do with funnels?

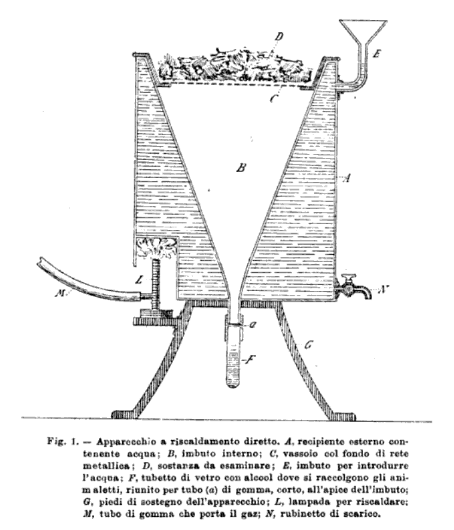

Well, as an entomologist, he devised a way to collect lots of soil-and duff-dwelling critters. In specific, his technique involved suspending leaf litter and other organic debris on a screen mesh in a funnel, and then heating its contents to dry. As they did so, the critters therein moved ever further downward until the funnel caused them to drop into a holding container (usually containing alcohol of one sort or another, which killed and preserved them). Here’s the illustration from his 1905 publication:

When electricity became widely available, it was a lot easier to heat a sample with a light bulb*👇 and, to this day, sampling duff and soil is frequently done using what have come to be called “Berlese funnels.” Here are some modern examples, both homemade and commercial.

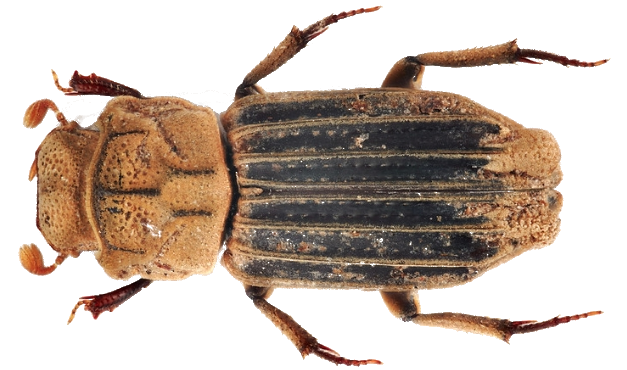

As you might imagine, most of the critters collected in this manner are quite small. In fact, there’s a whole world going on in that decaying debris! Take a look at this 5mm wide field of stuff in this morning’s sample:

Consider the above photo to be a “can you find it?” puzzle: Can you find: a beetle, several families**👇 of mites, a millipede, two spiders, and a collembolan (“springtail”)? Not shown, but also in this sample, were pseudoscorpions, thrips***👇, weevils (anther type of beetle), annelid worms, and some ants.

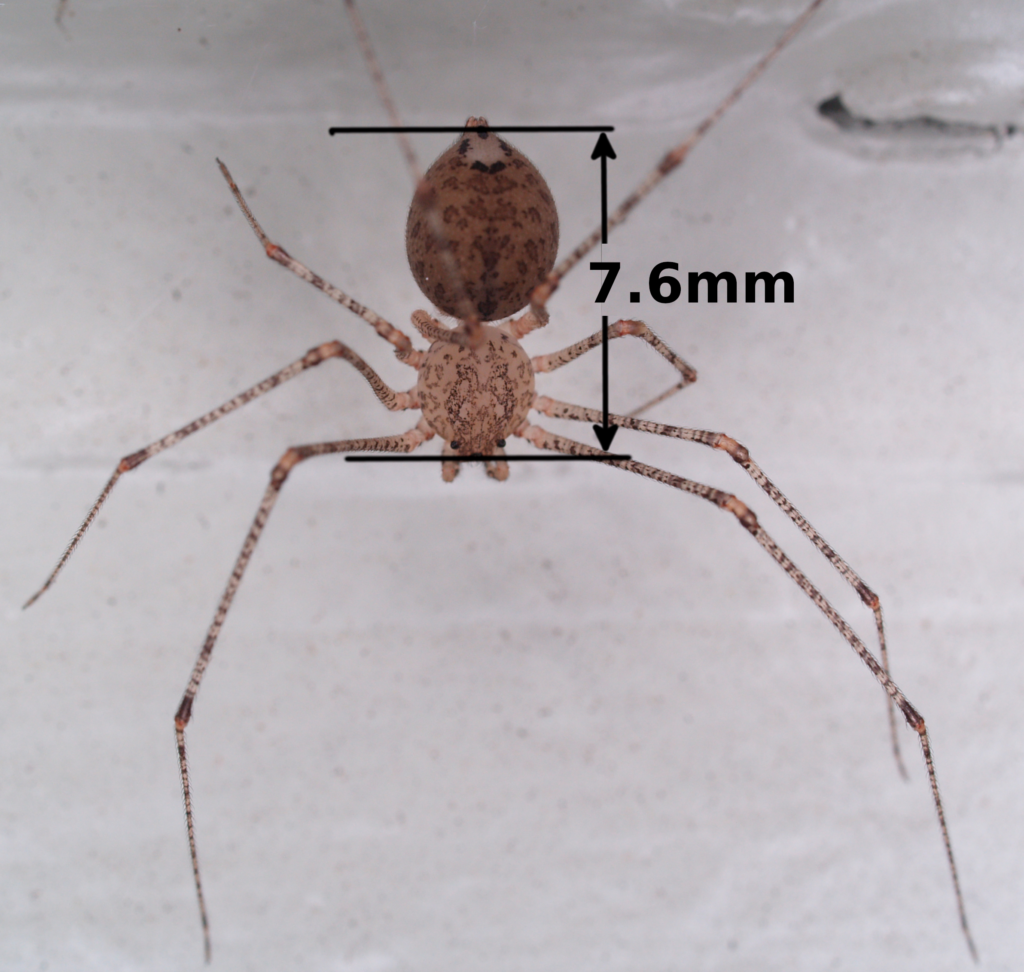

Now, to be honest, that small size can make specimen identification difficult.

E.g. here are some immature spiders: That big black thing coming in from the left is a plain old #2 pencil point to provide a sense of size (each of those glass beads is nominally 1mm in diameter):

Now, the technical term to describe spiders such as these is “really, really small,” and, in fact, at this writing I have absolutely no idea what many of them they are. If, as I hope to do, I turn up some adults, I may be able to identify these tiny guys by their markings or other characteristics that are maintained throughout their lives, but at this point, I simply—but quite lovingly, mind you— call them “Tiny, Non-Identifiable Spiders.”

The amazing thing to me is not that there is such a diversity of small critters: Instead I am in awe that there are so danged many of them. Every sample of leaf litter I scrape up contains all sorts of things in goodly number. I typically sample ca. 2qts of material at a time, from which I will find hundreds of little animals that had been going about their daily lives breaking down rotting vegetation…or eating the guys who do. Or eating the guys who eat the other guys, etc., keeping in mind Jonathon Swift’s satirical poem on poetry: A Rapsody, 1733:

So let’s give Sig. Berlese a well deserved tip of the hat****👇 for finding a way to view a bug-eat-bug world most people had no way of knowing about!

*👆 Incandescent. Or maybe halogen. But not LEDs, which generate almost no heat.

**👆

“Family” in the taxonomic sense; e.g. weevils are a family, jumping spiders are a family, great apes are a family (and yes, that includes us).

***👆 Oddly enough, the word “thrips” is both singular and plural.

****👆 But do people even tip their hats anymore? It used to be a sign of respect—even when expressed verbally!

Reference:

Berlese, Antonio. 1905. Apparechhio per Raccogliere Presto E in Gran Numero Piccoli Artropodi. Tipografia di M. Ricci, Firenze, Italia.