Many arthropods are masters of crypsis, either being camouflaged so well that they’re almost impossible to see, or being such good mimics of other organisms that they are very difficult to tell apart.

Today, I want to share some neat info about a moth larva that does a bit of both.

In specific, slightly more than four years ago, I walked out onto our deck to discover this large “inchworm,” i.e., the larva of a geometrid moth (also commonly called spanworms, geometers, cankerworms, or loopers) on the gate:

Now, I don’t have any idea what species this is. I didn’t kill the larva, so I really didn’t (don’t) have any way to determine it, so we’ll just be happy calling it a geometrid (that means it’s in the family Geometridae).

Anyway, pretty clearly it’s camouflaged really well to look like a twig; you can imagine that if this caterpillar had been holding onto a branch with its prolegs (the fleshy, false “legs” on the rear segments of most caterpillars) instead of a red-stained gate, I probably wouldn’t have seen it.

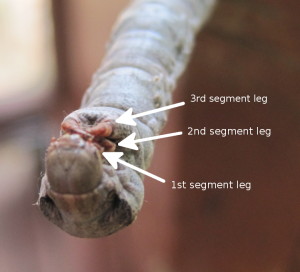

It’s hanging belly up so at the right end you can see where its six true (jointed) legs pointed are tucked in and pointed skyward.

So score a very strong point for camouflage.

But this beastie isn’t done–it turned out also to be mimicking a small snake.

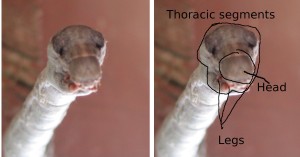

If we look at this critter head-on in this upside down shot you can see the faint Y mark of the head’s frontal sutures. This would be its “face”…if caterpillars had faces.

As caterpillars are larval insects, they have six true legs, one pair on each segment of the thorax. The way this caterpillar is hanging, you can see four of them partially: just to the right of the head is the very tip of the leg on its 1st thoracic segment, behind that a bit more of the leg on the 2nd thoracic segment, and then much more clearly both legs on the 3rd thoracic segment, which–perhaps significantly–resemble the forcipules (“poison claws”) of centipedes. (Click on photo to enlarge)

You can also see on the large, 2nd thoracic segment an obvious pair of eye spots. Remember, the head is that little thing with the Y. Those dark spots that look to be eyes are primarily on the 1st and 2rd thoracic segments, far from the head. Let’s turn that photo over and mark it up:

All of a sudden, we have the face of a snake. (Click on photo to enlarge)

But coolest of all, this “snake” defends itself by striking! Check out this video; watch what happens when I touch the prolegs.

Despite the fact that this caterpillar is absolutely, completely, utterly, totally harmless, when it first “struck” at me, I reflexively pulled my hand away! (Sorry for the out-of-focus video–it was impossible to see what I was getting…)

Now, I ask you: How can anyone see stuff like this and not just love insects?