Back on 01 August 2020, I wrote about finding a species of spitting spider, Scytodes atlacoya, in my home in central North Carolina, which species had not hitherto been recorded from this state. It occurs to me that I offhandedly mentioned that spitting spiders were appropriately named, but failed to elaborate.

The moniker “spitting spider” can be applied to any of the 245 species*👇 of spiders in the family Scytodidae, and it relates to their method of prey capture.

With the exception of a single family, **👇 all spiders have venom glands. The scytodids, though, have highly modified glands that produce not only venom but silk and what can best be described as “glue,” although I am prone to using the technical term: “stickum.”

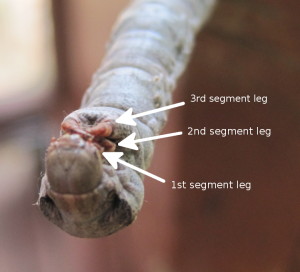

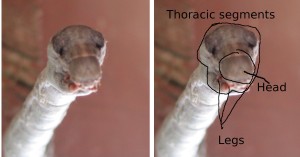

Most spiders’ venom glands are in the cephalothorax***👇 and connect to the base of each chelicera; the venom is then released through small holes in the pointy, business ends of the cheliceral fangs. In the evolution of their multipurpose venom glands, those of spitting spiders have become quite enlarged and take up a lot of space, giving the spiders a rather pronounced and distinctive humpedheadedness.

Scytodids have rather poor eyesight, so they use their super-long front legs as distant early warning devices, and as hunting range-finders. When they assess something in range to be potential prey, they spit their glue/silk/venom mix onto it through the holes in what are remarkably small fangs.

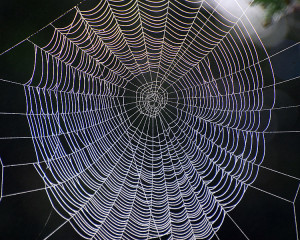

In doing this, they emit a stream of solidifying silk covered with stickum and venom. As they expel this mixture, the fangs oscillate rapidly, creating a zigzag pattern. As there are two fangs doing this simultaneously, the glop not only zigzags, but crisscrosses!

The silk not only solidifies almost instantly in air, it quickly contracts, which, owing to its gluey component, binds the intended prey and can also serve to stick it to the substrate.

After the prey has been rendered pretty much immobile, our spider approaches carefully and often loosely wraps it in more silk from its spinnerets. Eventually, using those tiny fangs, it nips through a thin spot in its prey’s “skin,” and injects its fast-acting venom to kill–or at least paralyze–it.

Then, the spider begins an interesting process of alternately forcing digestive juices through the fang-made-holes into the prey, and sucking out its liquefied contents through those same holes (spiders can’t suck anything through their fangs!).

To entertain you, here’s a silent, (don’t turn up those speakers!), real time, 35 sec. video I recorded showing a young S. atlacoya having captured, and now eating, an also young cobweb spider (you’re looking at the underside of the atlacoya‘s cephalothorax on the left):

- At ca. 3 seconds in, you’ll see some dark material being sucked into our atlacoya though the holes made by its fangs–watch the moving black spot on the prey: Our atlacoya is using the prey’s leg as a straw!

- Around 10sec in you can see the prey collapsing as its contents are being sucked out.

- At about 20sec you’ll see that atlacoya stops sucking, and instead forces more digestive juices into the prey, refilling the latter’s abdomen as if it were a water balloon!

- And finally, at ca. 25sec, you’ll see more specks of matter being sucked in through the leg-turned-straw.

And, just in case you’re wondering, the alternate sucking/refilling in that video occurred over 20 times during the more than half hour it took before atlacoya had sucked its victim dry.

*👆 i.e., 245 species of Scytodidae accepted by the World Spider Catalog at this writing, 03 Sep 2020.

**👆 The spider family Uloboridae, hackled orbweavers, is the only known spider group having no venom. They bore their prey to death with bad jokes.

***👆 Spiders have two distinct body segments. Their front end is a combination of a head and a thorax–i.e. cephalothorax, where cephalo=head, thorax=”chest.” The other segment is the abdomen. Insects, you’ll recall, have three such segments, the head and thorax being separate.

REFERENCE:

Suter, Robert B. and Gail E. Stratton. 2009. Spitting performance parameters and their biomechanical implications in the spitting spider, Scytodes thoracica. Journal of Insect Science, Volume 9, Issue 1, 2009, 62,